Balayer – A Map of Sweeping

2014

Imogen Stidworthy in collaboration with Gisèle Durand-Ruiz and Jacques Lin

and with the participation of Christoph Berton, Gilou Toche and Malika Bolainseur

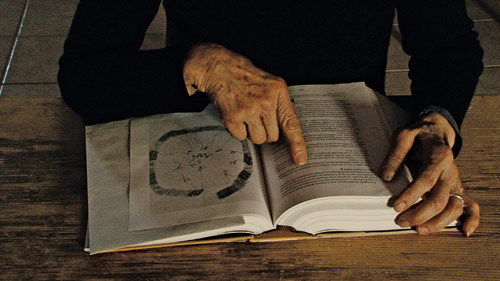

Imogen Stidworthy’s project for the 31st Bienal revolves around a network of temporary homes for autistic children set up by the French writer and pedagogue Fernand Deligny in 1967, around the village of Monoblet in the Cévennes, southern France. Rather than psychiatric care, it was an experience of communal living that was on offer in these farmhouses: therapists were replaced by untrained social workers, and isolation by life out in the open. In this way, Deligny sought to create an environment that responded to the children’s way of being-in-the-world, notably their withdrawal from language. Verbal communication was therefore dispensed with and visual tools such as map-making, photographs and films were used to interpret their gestures and wanderings.

Although the network ceased to operate in the early 1980s, Deligny’s collaborators Jacques Lin and Gisèle Durand continue to live with autistic adults in one of the farmhouses – two of these adults arrived as children in the late 1960s. Building upon her ongoing enquiry into the borders of language, Stidworthy has worked with them to consider the legacy of Deligny’s project and reflect upon what being without language might indicate about the ways in which language constructs our sense of self and thus structures – as well as restricts – our engagement with the world.

Each component of Stidworthy’s installation focusses on a particular cultural practice devised by Deligny in his attempt to take account of the relation with the autistic persons, and of their worldview – namely tracing, ‘camering’ and writing. Attentive to their heightened perception of the material world, Stidworthy has filmed them as they work with Gisèle Durand in a project that she initiates from time to time, involving tracing on paper – an activity that Deligny distinguished from drawing to emphasise its unintentional basis. A similar lack of purpose underpins Deligny’s notion of ‘camering’: an aimless filming that we can recognise in the installation in images made from a ‘detached’ and, to a degree, un-authored camera position. We also see unedited video recordings taken by Lin over years, raw material for a future film captured through an embedded, insider’s eye. Finally, Deligny’s unusual style of writing – here translated live from the French – reveals his attempt to defy language within language. His struggle to counter the rules of the written word thus dovetails with Stidworthy’s own efforts to question the neutrality of language. – HV